I

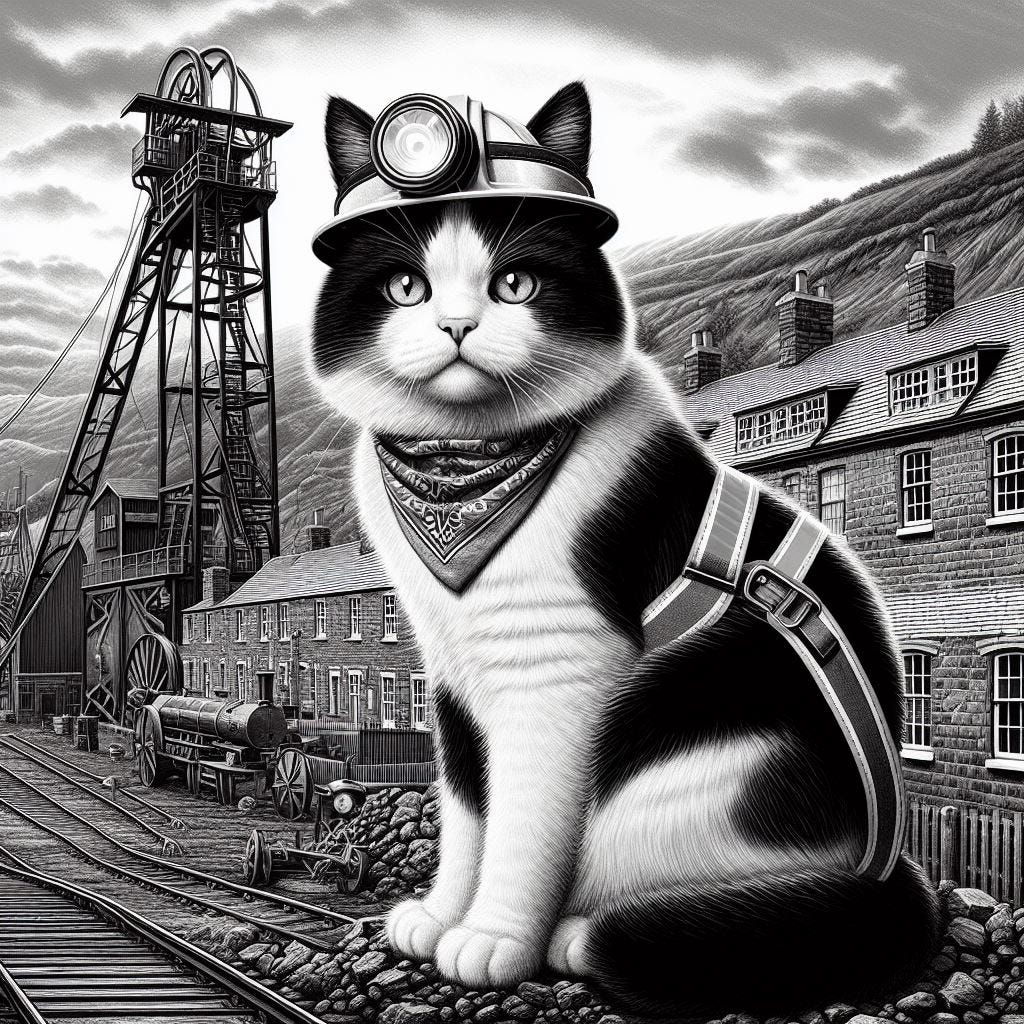

What connects the ideology of the little feline that my cat Nummy inspired, and the UK coal miners' strike of 1984-1985? Although The Little Feline began producing essays in 2024, the ideas that influence it date back to the 1980s.

The miners’ strike was a pivotal moment in history. Although the Conservative government, first elected in 1979, had already adopted economic policies that overturned the post-war consensus of an economy where profitability was balanced with social considerations, the numbers involved in the miners’ strike and its impact on these communities of pit closures was the biggest demonstration that government assessed human value in purely economic terms and therefore social and communal concerns surrounding job losses were of no importance.

The miners’ strike was a watershed moment. From that moment on, both subsequent Conservative and Labour governments placed “the economy” as separate from and superior to the welfare of the people they were elected to serve. This shift from a viewpoint that government had a responsibility to manage the economy on behalf of the whole population to one where individuals were expected to serve an economy that reserved its greatest benefits for a minority, is one I witnessed at first hand during the 1980s. Although the shift had begun to happen after the Conservative election victory in May 1979, the miners’ strike was the final demonstration that the state considered the population purely in terms of economic utility rather than as valuable in themselves.

When elected in May 1979, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher quoted from St. Francis’ prayer, “Where there is discord may we bring harmony.” By 1984, it was clear that the harmony her administration sought was one which left behind those deemed unprofitable. In her government’s view, individuals alone were responsible for their circumstances, and if those circumstances were bad, the blame lay solely with the individual. Prime Minister Thatcher famously remarked later “Too many people are casting their problems on society. And who is society? There is no such thing!” She went on to talk of how society is formed of individuals and families and that people naturally take care of their own interests first.

In contrast, as Nummy was a domesticated cat, she relied on her community—my wife and myself—to meet all her needs. For her to flourish we had to invest in her food, pet supplies and vet visits. We also had to give up our time to her, for example, to play with her, or be available for her to sit upon our laps. We had to stroke her and pet her. In short, we valued Nummy for her own sake. Nummy produced nothing of value; she cost us money rather than making money for us. Despite her “unprofitability,” and despite the lack of material benefits she provided, we cared for Nummy right up until she passed away. It was absurd to think we’d allow her to fend for herself.

Yet, when the National Coal Board announced the closure of twenty pits and job losses of 20,000 workers, the government expected those miners to survive without support.

The coal mining communities of the UK depended on the employment that the pits provided. These pit villages owed their entire “raison d’etre” to their mine. All the retailers in the village depended for their business on the wages the miners spent. Local industries sprang up to supply the machinery and tools that the extraction of coal demanded. The pit was a harsh and dangerous working environment, but it guaranteed the possibility of a working life to stretch from leaving school to retirement. Even leisure pursuits centered around the mine’s existence; many of Yorkshire’s brass bands bore the name of a pit—like the Grimethorpe Colliery band. The same was true of the male voice choirs of the mining villages of South Wales; their members were mostly miners. The deposits of coal were the sole reason for the existence of these communities.

The pit villages represented a different kind of community from that of larger cities with a variety of industries and professions. Everyone either worked at the pit, or was married to a miner, or did business with the colliery. If the mine disappeared, the community went with it. It would become like a destroyed antheap, with people losing their knowledge of who they were. One may say that this identification with the mine was a superficial one, that as humans they were far more than mineworkers, but the mine provided purpose and direction. The common interest of the people in working there led them to a concern beyond their own individual worlds. There was an empathy, a support for one another that was lost in cities where people lived side by side but had much less in common and so could not understand another’s situation. If a member of the community was struggling, their neighbors would most likely provide support.

Up until the miners' strike there was a slimming down of the coal industry from the late 1950s as coal seams became exhausted. Mines closed, but this was done in consultation with the miners who then received generous compensation and help with retraining and finding other employment. This approach meant that the communities where the pits were located were also sustained. From a financial viewpoint, this was inevitably costly to the industry and to government. The justification for these costs rested in a belief that viewed the inhabitants of the community as more than what they produced.

These policies supported the intrinsic value of human beings, not solely derived from what they could produce. This earlier treatment of miners whose pits were being closed is a vivid example of the meaning of the term “welfare state.” The “welfare state” believed in the inherent value of the human being, a value independent of economic activity, an expression that the human was valued for his or her own sake. As Lisa McKenzie, a miner’s daughter, who was sixteen when the miners' strike occurred, said in a recent Observer interview, “The pit was life, it was everything. We might not have had much money, but we were honest folk. Love and safety and security: 1984 to 1985 removed all of that.”

“Love, safety and security” are three pillars on which a vision of fully flourishing humanity is built. These three values were expressed in the way we cared for Nummy. Whenever Nummy had a need for food, water or companionship, we met it. Nummy was an indoor cat who was frozen in fear if she escaped outdoors. When we first moved into our house, she escaped outside and sat rigid on our back deck’s step. I found her and brought her back inside and once there she visibly relaxed.

It was natural that we should exhibit these values in caring for our family’s pet. Why should anyone believe that we should treat any member of the human family with less dignity than that? As human beings, the miners, their families and communities were deserving of love, safety and security from those who held power over their lives.

These values were ones that democratic government, which derives its legitimacy from the will of the people, should have upheld. The National Coal Board argued the pit closures were necessary because the price of coal meant the industry operated at a loss which the British taxpayer had to bear. The closing of the pits, though, meant that the British taxpayer had to pay for unemployment benefits and the consequences of the pit closures to their communities.

Wouldn’t it have been better stewardship for the country as a whole if resources were directed to helping these communities to move away from dependence on coal mines by attracting other industries and retraining the miners?

The miners knew that if they lost the strike and the pits closed, there were no immediate alternative options for employment in their communities. Since the government viewed the unemployed as morally deficient, the miners and their families could only expect limited help. They knew their communities would therefore become economic wastelands and this hopelessness would flow down to their children and further. All these factors led to the intense violence associated with the miners’ strike, most notably at the “Battle of Orgreave” on June 18, 1984.

The government was determined to use every means available to defeat “the enemy within” in Margaret Thatcher’s words because the striking miners and their wives and children represented the fullness of human dignity. In the same way, nearly two hundred years earlier, troops were sent out in the name of millowners to defeat the Luddite handloom weavers. Violence is an inherent part of any society that wishes to reduce humans to units of production.

With the whole weight of the state ranged against them, what is surprising is that the miners held out for nearly a year until March 3, 1985. The crushing of the miners' strike was the prelude to the defeat of other organized groups of workers, such as the printworkers in the dispute with Rupert Murdoch’s News International. Margaret Thatcher’s defeat of unionized workers removed most obstacles from treating their workers as “human capital” instead of “human beings.”

II

The consequences of the miners' strike are still felt forty years later, most directly in the former mining communities. For those who endured the strike, who saw their pits closed down and the communities that sustained them fall apart, these consequences included sackings and blacklists, divorces and suicides.”

Forty years since the miners' strike began, those communities which are the most deprived, which include the former mining villages, have a much higher rate of suicide than the least deprived, according to a recent House of Commons briefing paper. “People living in the most deprived areas of England have a higher risk of suicide than those living in the least deprived areas. The suicide rate in the most deprived 10% of areas in England in 2017-2019 was 14.1 per 100,000, which is almost double the rate of 7.4 in the least deprived decile.”

The miners' strike and its defeat has implications far beyond its time and place. Up until the mid 1980s, there was a political consensus that the government's role was to ensure the good of everyone in society. This had the beneficial effect that it offered any person the opportunity to follow their highest calling and develop their full humanity. It was the same kind of community that we offered Nummy; one that allowed her to be her true self.

There is, though, a lie that also can deeply influence humanity; the lie that says we are separate from the universe and from others. This lie tells us that we live in a universe of scarcity, that societies that seek to serve everyone’s highest good, cannot exist. Moreover, this lie suggests that a successful society requires a ruling class to control and direct those ruled. In this view, human beings are incapable of co-operating for their mutual benefit. However, David Graeber and David Wengrow argued convincingly in The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (2021) that archaeological evidence shows that many ancient societies across the world were structured on egalitarian principles and cared for all their members. In some cases, these societies endured for many centuries.

It was not, therefore, inevitable that a society which pitted individuals against one another should be the only one that could successfully continue. Forty years later, the rise in global temperatures to levels that endanger the human race’s future, demonstrates that the planet cannot sustain unlimited economic growth. Reversing and mitigating the effects of climate change requires a global, communal response. Individuals alone cannot take meaningful action to control planetary warming.

Yet, as we saw earlier, the people who lived in the mining communities spoke of the “love, safety and security” they knew growing up. Although the work was extremely dangerous, because of this it was well paid. It offered work that was secure and stable. When the pits were closed and no thought was given to sustaining the communities that the pits supported, the consequences included the breakdown of human relationships. Where once proud men had the dignity of their labor and were fulfilled in their work, now they sat at home on the dole, or desperately sought jobs, competing with hundreds of others. Even if they managed to find a job, they would have little say on their conditions of work.

The fate of the miners is the same that everyone who is not born into the privileged elite faces. We are taught from early childhood onwards that life is a competition and that other people are a threat. Even love is subject to economic considerations. Human life is subordinated to the demands of “the economy.” Human value is derived only from how productive we are. In previous generations, cathedrals of incredible beauty were raised to glorify God. Their intricacy continues to astound generations. What are the monuments that future generations will see to mark our present age? Are they the communities that have the highest levels of deprivation in the UK, the former mining towns?

We gave more care to our cat than a government that claimed to serve the people gave to the miners and their families. We created a community that gave Nummy love, safety and security. Margaret Thatcher’s government took that love, safety and security away from the miners and their families. Governments everywhere have enabled a society where life for most of their people is a competitive struggle for survival. The full dignity of the human being is subordinated to the demands of “the economy.”

This is why The Little Feline exists. It’s time to create an economy that serves humanity rather than subject humans to an economy that keeps them from experiencing their full glory.

© 2024 Phil Kemp

As you know this is very real in the area I live in. I’ve just come in from Durham Cathedral and one of the places where we prayed was the miners’ memorial which was set up as a memorial for miners who died in the course of their work but has become a memorial to a whole way of life. It was used to represent Jesus falls for the second time in the stations of the cross.

Excellent, Phil. I really like this. Thank you